In modern software development, a project isn't a project without a proper versioning scheme.

Weak version management neglects clients like lack of source control

neglects collaborators. Dependency management and migration rely on

versions. Beyond the technical, a project's version bears a huge

impact on the perception of the project. It informs adoption and

entices users to upgrade. The version is attached to the name of the

project — appearing closer and more often than the names of the

maintainers. Versions are how a project builds a legacy.

Weak version management neglects clients like lack of source control

neglects collaborators. Dependency management and migration rely on

versions. Beyond the technical, a project's version bears a huge

impact on the perception of the project. It informs adoption and

entices users to upgrade. The version is attached to the name of the

project — appearing closer and more often than the names of the

maintainers. Versions are how a project builds a legacy.

So why do projects leave versioning to afterthought? What do clients expect and what do projects need?

Semantic Versioning

Currently, the go-to versioning system for open-source software is referred to as Semantic Versioning, or SemVer.

Take a quick look at the

40 most recent updates on the Python Package Index

(PyPI). My glance showed all but six packages had the

comfortable three-part versioning scheme, major.minor.micro. Among

those packages the highest minor version was 108. The highest micro

version was all the way up to 595.

So, if SemVer is so popular, it must be easy, right? Follow a couple straightforward steps. Pick a number, add one to it. With arithmetic that simple, what could go wrong?

SemVer and code breakage

Everyone knows it's more exciting to announce 2.0 than 1.7.0, even if there's more user demand for the latter than the former. This is especially true with SemVer, because a SemVer major version change implies breaking the API.

As we will see, there are consequences to this. People judge value based on version number. SemVer supports this opaque apples-and-oranges comparison, punishing libraries that get it right on the first try, and encouraging libraries to break APIs to appear more mature and get that coveted 2.0.

SemVer and release blockage

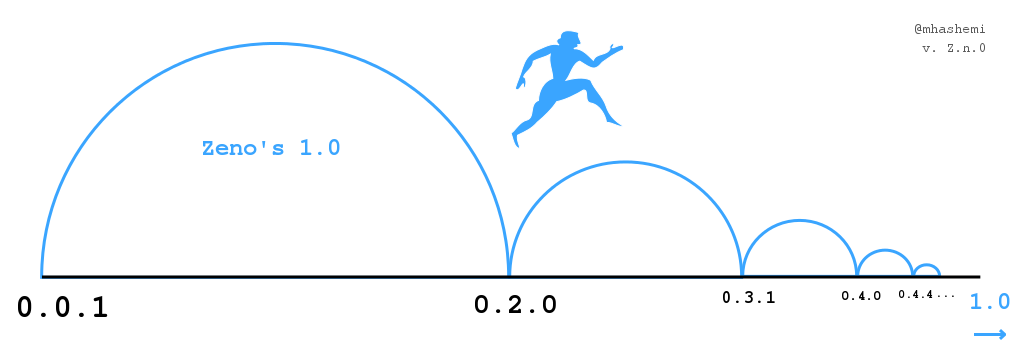

More damaging than the fatuous 2.0 is the epidemic of Zeno's 1.0.

Witness the version, racing to numeric motionlessness. (Image based

on Martin Grandjean's.)

To quote the second answer in SemVer's own FAQ:

If your software is being used in production, it should probably already be 1.0.0. If you have a stable API on which users have come to depend, you should be 1.0.0. If you’re worrying a lot about backwards compatibility, you should probably already be 1.0.0.

On this count, SemVer might be found not guilty.2 If so, it's the SemVer users that didn't get the memo — myself included. Maybe if it had been in the spec itself.

The problem is the heavy emphasis on "public API" breakage. Conservative library authors end up indefinitely preferring the semantic power of 0.x: The ability to break APIs. Whether the cause is conservatism, humility, or misunderstanding, the effect is misrepresenting the release state of many major libraries.

A more practical scheme might help represent accurate versions for mature, production libraries like Cython (0.23) and SciPy (0.17), both of which havebooks and nearly a decade of release history still on PyPI.

SemVer and certifiability

Appealing to engineering aesthetics, SemVer is presented as a "specification". But, unlike the vast majority of successful RFCs, there is no validation or certification that can determine whether a project has a correct implementation. Yes, if a project API changes, but the major version is not incremented, the SemVer specification has been violated. But there's no way to test that generally, and no one does it specifically.

SemVer is a detailed suggestion. Software breaks as quickly as SemVer's promise. The remediations do not happen. Better to embrace the realities of versioning, rather than argue over the MUSTs and MUST NOTs of an unenforceable specification.

Collective Expectations

Let's take a brief moment to reconsider the humble version.

We encounter far more software than we write. Few, if any, expect compliance with all the suggestions in SemVer. So what do we expect from our versions?

There are three main expectations driving modern software versioning:

#1 Versions go up

The later the release, the greater the version. Sofware should not change without a version change, and the version must go up, and never come down.

#2 Versions correlate to software quality

A project name communicates an ideal. The project version communicates current progress toward that ideal. Vision pursued by version: The greater the version, the greater the software.

#3 Versions are numeric, except when they're not

Here's where things get hairy. Numeric versions are the default, but non-numeric versions and version components abound.

Version vernacular is now thoroughly mainstream: "alpha", "beta", "dev", "nightly", "stable", and so on. There are also named project versions, like those used in Linux distributions, such as Debian's "jessie", Ubuntu's "trusty", and Windows' "longhorn". Non-numeric versions are often hijacked for branding purposes. Numerical versions' technical utility is much more important to preserve.

Case Study: Chrome vs. Firefox

We take our version expectations for granted, but a convention this fundamental has profound effects at scale. As mentioned above, higher versions are expected to be better, especially within a project. But there is at least one case where this impact very publically spilled out across projects: The Chrome-Firefox Version Wars.

When Google Chrome entered the browser race, it brought with it a fast feature release schedule and a versioning system to match. This versioning system had Chrome see a dozen major releases while Firefox was still 3.x. Firefox looked like it was being left in the dust, despite the fact that Chrome was less mature and, as anyone who used it at the time can attest, Chrome 4 wasn't half the browser Firefox 4 ended up being.

After a couple years of this onslaught, Firefox switched its versioning system to match. Now, despite browsing for hours a day, few users or even developers could tell you off the top of their heads what version of Firefox/Chrome they use.3

SemVer ignored this huge precedent, harshly judging fast-moving projects. Let's call that our last straw and look at an alternative.

Calendar Versioning

If you're an earnest engineer with honest intents of creating,

releasing, and maintaining a project, then calendar versioning may be

for you. It fulfills all of

the versioning expectations, so what

advantages does it bring?

If you're an earnest engineer with honest intents of creating,

releasing, and maintaining a project, then calendar versioning may be

for you. It fulfills all of

the versioning expectations, so what

advantages does it bring?

CalVer leverages natural understanding

People are calendar-oriented. Practically, it's just easier to remember that a library was causing a live issue back in 2013 than it is to remember that up until version 1.6.18 that library had a lot of bugs.

Furthermore, in long-term development, releases pile up and increasingly large major versions blur together. Browser versions have been rendered meaningless. But the calendar is one construct where numbers increase and cycle regularly. Leveraging that natural understanding anchors otherwise arbitrary versions.

CalVer has better semantics

Ironically yes.

"Semantic" Versioning is all relative. One developer's 1.0.0 is another's 0.0.1alpha. As authors, we try to ignore this and write others off as wrong. But as clients, we make snap judgments, and SemVer lets us forget and pretend. Calendar versioning is absolute and neutral, with practical advantages to boot.

As application developers adding functionality, evaluating a new library means ascertaining maintenance status, usually by looking at the most recent release date. CalVer puts us in the ballpark right away. As maintainers depending on many libraries, calendar versioning allows us to look at the dependency list and quickly ascertain which libraries are good candidates for updating. CalVer even lets us take that a step further, with date-based deprecation.

Many might not realize it, but the oh-so ubiquitous Ubuntu

is in fact calendar versioned. For example, version 15.04 came out in

April, 2015. It gets better when you remember Long-Term

Support. Ubuntu's LTS support lasts for five years. So, 14 + 5:

Ubuntu 14.04's end of life will be in 2019. You don't have to look

anything up. It's all right there in the CalVer semantics.4

CalVer protects projects

If you care about the future of the project, then guard it against one of the worst fates: the fatuous 2.0. Give your project a future. Guard against the learned expectation of 2.0 or death.

A 1.x always carries one advantage over a 2.0: the code is deployed and working. Avoid contempt for past decisions and current users. In engineering, utility is half of correctness.

SemVer is set up so that every major release implies a minimum threshold of change. If the project is founded on and aiming for correctness, fewer and fewer changes are required. Donald Knuth embraced this in the extreme by having TeX's version approach π asymptotically. Suffice to say with CalVer, you are safe to add as much or as little functionality as needed.

Too often projects become a victim of versioning. New projects end up masquerading as new versions. D3 could have been Protovis 2.0, but instead, a successor was created. Both projects coexisted and we are all the better for it. Same with characteristic and attrs. Successors and CalVer protect projects and do justice by clients and code.

Summary

Consider adding a calendar component to your next library's versioning schemes. As for my opinion, I've joined othermaintainers in doing so for boltons and ashes. I've found it makes a lot of sense for libraries, and a little less sense for protocols and services.5

Either way, think about project versions. The version is part of your project's face and your clients' integration. After spending days, weeks, and months on a project, it's worthwhile to spend a few minutes or hours designing a versioning system tailored to the needs of project users and maintainers.

If you're into enterprise software considerations like these, subscribe or follow me on Twitter for some details about my upcoming O'Reilly project.

Astute readers will note that it's Semantic Versioning 2.0.0. "Oh, cute, Tom used his own scheme for the document." But did you wonder what public API changed to trigger that major version bump? SemVer's public API has been semver.org since before 1.0. How about those semantics? ↩

I've actually been saying something similar, but more practical, for a long time:

If both you (or your team) and a stranger (someone not directly advised) are both using a library in a production environment, the time for a major version has come.

If it's just you and yours, that's understandable. Many great scientists took great risks with themselves for the sake of progress. If it's just a stranger going against your explicit advice, then there's no accounting for such wildcards. But, if both of groups are using something in production, then it's time to face the facts. Tie up the loosest of ends and give it a major version. ↩

Here are some more resources for those interested in the Firefox release switch up:

- Support forum discussion on FF major releases

- Firefox Rapid Release Criticized

- Former Mozilla dev Jono DiCarlo on Firefox Rapid Release

- The Bugzilla bug for hiding the version number

At the very least this should illustrate that versions matter. They're part of your project's identity. Design them to help your user. ↩

To illustrate the prevalence, there are actually many other examples of calendar versioning we take for granted. Off the top of my head I could think of Twisted, Windows 95/98/2000, and probably most ubiquitous: every mainstream car in circulation. Email me with more examples and I'll compile them somewhere. ↩

To illustrate, if I could have it my way, we'd have OpenSSL 16.x.x. That way I can easily complain if I find someone using 10.x.x in production. That said, TLS/1.3 seems better than TLS/16.0.

My current thought is that protocols live outside of time, because I believe it's possible to complete a protocol, but an implementation is never done. ↩